Why the University of Sheffield’s problems are made in Sheffield

University management claims the current financial situation is entirely down to external factors. The evidence suggests otherwise.

Early in summer 2024, staff at the University of Sheffield were warned that recruitment of international students was forecast to be dire, and that bad times were coming.

Once students had arrived in the autumn the scale of the crisis was clear, with over 2,000 fewer international students registered than expected. At tens of thousands of pounds a head in tuition fees, the University was staring at a £40-60m hit to its income. The bad times had arrived.

The Vice-Chancellor (VC) was at pains to stress that this was a crisis facing the whole sector, citing immigration policies, competition from other countries, and geopolitical change in key markets among other things. While the crisis had affected us, we were told that the prudent financial management his board had provided left us better placed than other institutions to weather the storm.

The overall message was that while there would be tough times coming, the cause was circumstances outside of their control. We should believe that the institution had been well run to this point, and the VC would provide the safe hands to steer us through.

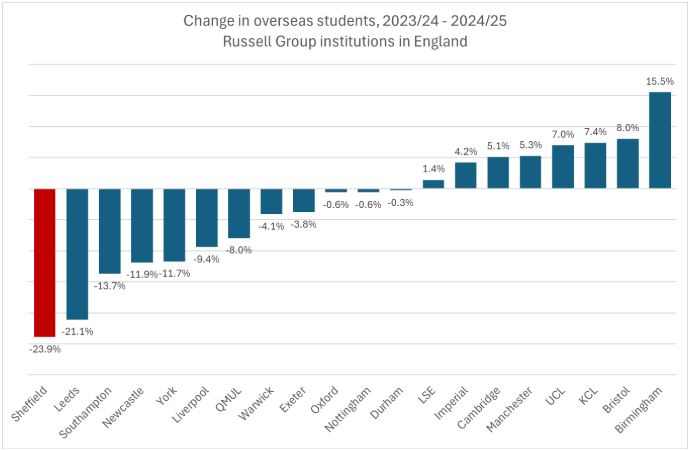

But the evidence started to build that this narrative was dubious. While we had lost around a quarter of our international students, it was known that other similar universities had seen growth, not decline.

In December 2024, the Guardian reported that the Universities and Colleges Admissions Service (UCAS) data showed a fall of only 1.9% in Chinese undergraduate registrations. By the time the Office for Students released their Higher Education Students Early Statistics (HESES) survey data at the end of February 2025, the real picture was laid bare: Sheffield had been hit way harder than average, and had topped the Russell Group in a table no-one wanted to lead.

| Overseas students | 2023-24 | 2024-25 | Change |

| Russell Group* | 204,820 | 201,700 | -1.5% |

| HE Sector | 557,925 | 524,560 | -6.0% |

| University of Sheffield | 10,075 | 7,665 | -23.9% |

Source: HESES24 and HESES23

* Data not available for Cardiff, Edinburgh, Glasgow, Belfast

Analysis of the HESES data shows that the sector as a whole saw a 6% decline in international students in the current academic year. The Russell Group universities show a huge variation of outcomes. The University of Birmingham saw an increase in international students of over 15%.

Only five Russell Group universities saw double-digit falls, with Sheffield the hardest hit, and only Leeds anywhere close. In aggregate, the Russell Group lost just 1.5% of its international students. Sheffield lost a quarter.

Not only that, but the sector-wide falls in international students are driven primarily by declines in the numbers of Indian and Nigerian students. Sheffield’s fall, which has come about mainly from a drop in applications from Chinese students, is far, far worse than the national trend.

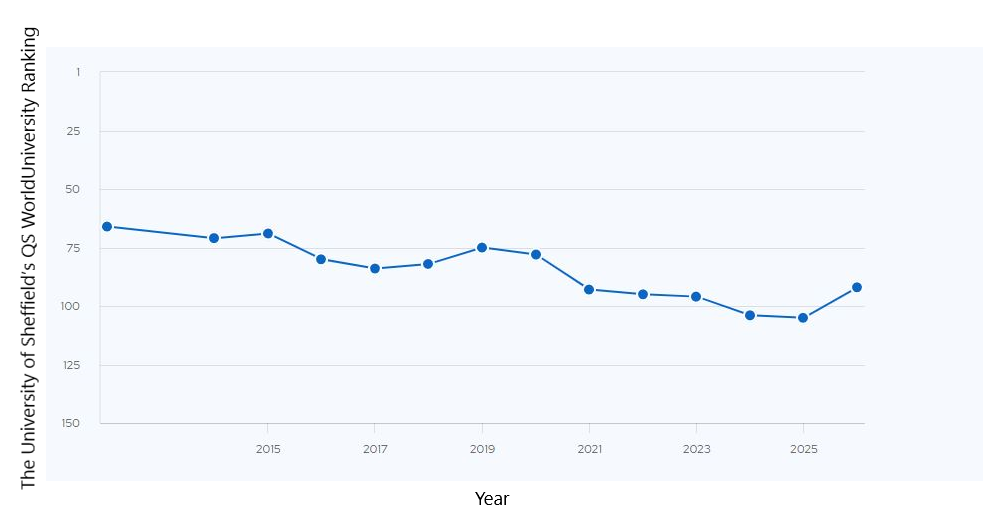

So what caused the recruitment crisis at Sheffield? The smartest guess is that it is due primarily to the University’s slow slide out the QS World University Rankings Top 100.

When Koen Lamberts arrived as Vice-Chancellor in late 2018, Sheffield was ranked at 75. Between 2019 and 2024, the ranking fell every year without exception. Finally, and predictably, Sheffield slipped out of the top 100 in June 2023.

Source: The University of Sheffield’s QS World University Ranking 2012-2025

It’s known in recruitment circles that a top 100 QS ranking is crucial to the desirability of an institution for Chinese students. Yet the first staff as a whole heard about the importance of this metric was after the University had left the elite list.

A lacklustre ‘reputation’ campaign to reverse the trend and get back in with the big hitters could only limit the damage to sliding one place further in June 2024.

When the scale of the harm to recruitment became clear, significantly increased efforts were put into targeting the reputation metric. Second time around, the campaign was a success and contributed to a leap of 13 places, bringing Sheffield back inside the top 100 in June 2025. But the complacency over the importance of the rankings to the University’s financial health had already left its mark.

There may be other self-inflicted wounds. In the summer of 2023, the University launched an institution-wide restructure of its Student Recruitment, Marketing and Admissions staff which, when it concluded, left the function hollowed out: at one point, there were over 70 unfilled vacancies due to an exodus of staff who left the university rather than go through yet another change management process.

Many of the remaining staff reported feeling overworked, demoralised, and under-supported. We warned at the outset of the dangers of carrying out such a large-scale restructure of an important university service.

While we’ve no doubt of the talent and efforts of the staff working in recruitment, even in these thankless circumstances, our knowledge of the damaging nature of this restructure leads us to suspect it won’t have had a positive effect on the recruitment cycle that precipitated the problems.

What should we make of this? The problems facing the University of Sheffield are not the same as the crisis facing the sector as a whole, but are primarily a result of decisions taken here.

The University’s finances were strong going into the recruitment downturn. Sheffield has racked up monster surpluses in recent years based on its bumper recruitment of international students, and generated huge amounts of cash from its operations which could help to see it through lean times.

The pressures caused by poor government policy also haven’t helped. But our recruitment crisis is primarily a result of over-reliance on a single country (China), a metric that we didn’t pay adequate attention to until it was too late (our QS ranking), and an ideologically driven urge to restructure, despite the mounting evidence of the damage it causes.

New Schools, programme simplification, and academic and non-academic restructures won’t solve Sheffield’s recruitment crisis, but a motivated workforce who feel valued and secure in their jobs and have confidence in their management might.

While the reputation campaign has taken us back into the QS top 100, and is likely to bring with it financial breathing space, we must remember that it was, ultimately, a vacuous gaming of the system that brought it about.

Moreover, the damage wrought by the extensive programme of staff cuts and restructures introduced in the wake of the drop in international students is likely to be much more lasting, especially given the targeting of key recruitment teams and academic expertise in areas of strategic importance (e.g. School of East Asian Studies).

Our current VC led us into these troubled waters. To cement our place in the world’s top 100 universities will require genuine enhancement of the University as a place of research and education, and there is little evidence that he has the skills to bring that about. The frenzied restructuring we’re seeing at the institution is on a scale never experienced before, and will cause untold damage to the institution.

But most of all, what we should take from this is that we must not let a good story get in the way of the truth. The University of Sheffield’s problems are made in Sheffield, however much those at the top try to lay the blame elsewhere.